In a secular culture like ours, there is no love for the great transformational movements of our past. Hollywood and history departments create the impression that God had nothing to do with the real issues of human struggle, that Christianity is all pie in the sky.

While many Christians today bring this judgment on ourselves by defining the Gospel as mere fire insurance, the fact remains that the principles of transformation articulated by George Otis and the Transformation partners have been in operation all along, and are clearly evidenced in history.

Slavery

The abolition of slavery provides a case in point. In this essay, I will show three abolition movements that were unsuccessful, followed by three that succeeded in actually getting rid of slavery. The latter three were those that followed the principles of transformation. That is, they advanced the Kingdom of God on earth in the way that Jesus recommended to us.

By contrast, the former three movements did not. They were mere slave revolts. Of course, Hollywood loves to glorify “the longing in the human heart to be free,” but it fails to add the important information, “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.”

Spartacus

My favorite movie during my teen years was Spartacus, starring Kirk Douglas. It really caught my fancy. The historical facts are these:

Spartacus lived during the first century B.C. (109-71), prior to the Caesar dynasty. He was a Thracian soldier in the Roman army who was caught deserting his post, and was rewarded with an educational scholarship. He was placed in a school that taught him how to entertain the aristocrats of Rome as a gladiator.

Spartacus lived during the first century B.C. (109-71), prior to the Caesar dynasty. He was a Thracian soldier in the Roman army who was caught deserting his post, and was rewarded with an educational scholarship. He was placed in a school that taught him how to entertain the aristocrats of Rome as a gladiator.

The old inclination to desert once again gained the upper hand and Spartacus began to make plans for escape. He staged a revolt known to historians as the Third Servile War. Using kitchen knives and meat cleavers, seventy slave-gladiators forced their way out of training camp and holed up in the hills above the Bay of Naples. There, Spartacus became a magnet for hundreds of escaped slaves yearning to be free. Eventually 120,000 slaves formed themselves into an army to win their freedom, and perhaps to build a slaveless Rome.

However, one of the great generals of ancient Rome, Pompey the Great, proved to be no fan of transformation. He challenged this army of slaves at the height of their power and defeated them. A great slaughter followed. The 6000 captives who were brought back to Rome were crucified along the Appian way. Their bodies, slowly decaying and pecked at by crows, were left hanging there for months as a lesson to all who travelled to Rome—and their slaves.

End of story. Rome kept on doing slavery, totally unrepentant. As transformations go, give it an E for effort. Effort may be worth admiring, but aren’t we interested in seeing some actual success?

Toussaint Louverture

Let’s zoom to the 18th century now, to the more familiar enslavement of Africans to serve in the white man’s plantations in the New World. Toussaint Louverture was an African Spartacus, with two differences: he was not a slave when he got into the struggle, and he succeeded militarily where Spartacus did not. His leadership places him in the ranks of the most brilliant leaders of all time, and he is almost always presented as the one and only person to stage a successful slave revolt. Wikipedia describes his victory in these glowing words: “His military genius and political acumen transformed an entire society of slaves into the independent state of Haiti. The success of the Haitian Revolution shook the institution of slavery throughout the New World.”

High praise indeed. A transformation seems to have happened! Or did it?

High praise indeed. A transformation seems to have happened! Or did it?

The Haitian revolution began when a Vodou priest and Islamist named Dutty Bookman held a secret meeting in a large grotto on the island known to the French as Saint Domingue, where there had been slavery ever since the son of Christopher Columbus had introduced it. He was joined in the grotto by Mambo Cecile Fatiman and a thousand slaves. According to the official account, Bookman inspired them with this speech:

The god who created the sun which gives us light, who rouses the waves and rules the storm, though hidden in the clouds, he watches us. He sees all the white man does, the god of the white man inspires him with crime, but our god calls upon us to do good works. Our god who is good to us orders us to revenge our wrongs. He will direct our arms and aid us. Throw away the symbol of the god of the whites who has so often caused us to weep, and listen to the voice of liberty, which speaks in the hearts of us all.

During the frenzy of excitement that followed this speech, according to this account, Mambo Cecile Fatiman became possessed by Erzulie 7 Kout Kouto, “the most dangerous manifestation of Erzulie Dantor. She drinks blood…A black female wild pig is presented to her, in symbol of liberty. Liberty is suppose (sic) to be free and untamed, as is the wild pig. The pig is stabbed 7 times and all participants soak their fingers in the blood, taking the oath to…live free or die.1

With no further ado, the whole crowd rushed out and attacked every white person they could find, killing them with crude weapons they had brought for the purpose, and burning their homes to the ground.

As this crude revolt grew, being supported by the Spanish against the French, a free black by the name of Toussaint joined its ranks as a doctor, then moved into a position of leadership under Georges Biassou, an early leader who had gained control of part of the island. Soon Toussaint was providing military leadership. He gained the name Louverture, because as a military leader, he had a way of finding military openings where at first none could be found.

With the arrival of the French Revolution in France, Toussaint soon adopted the motto of “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity” and switched his allegiance to the new leaders of France. Those in the movement still loyal to Spain were sifted out of the revolution, and Toussaint became the leader of the movement. After forming an alliance with the new French leaders, Toussaint was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Saint Domingue.

During the following years, a conflict developed between Louverture and the French authorities over whether former plantation owners should be allowed to return to their plantations to help build the new slaveless economy. Toussaint wanted them back. The revolutionary Frenchman, Sonthonax, did not. Toussaint won the power struggle and increased his position as governor over Saint Domingue. He was a skilled and just governor. During this period at the close of the century, he was making treaties with major world powers. At this time, a black soldier named Jean-Jacques Dessalines became a trusted leader of Toussaint’s armies.

At the turn of the century, Toussaint took control of the entire island on behalf of France, driving the Spanish off the Santo Domingo side of the island. This happened just as the French were tiring of revolution, and were turning to a man named Napoleon to save them from it. Suddenly emperors were in vogue.

Louverture appointed a new constitutional assembly composed mostly of former white planters, while he himself became governor for life over the island of Hispaniola. His ability to form alliances that overcame ancient hostilities was extraordinary. He also urged his African citizens to abandon Vodou and embrace Catholicism. This did not go so well, insofar as it was the Catholics who had introduced slavery in the first place. The new constitution guaranteed equal treatment of all races under the law, and outlawed slavery. It also made Catholicism the official religion of Hispaniola.

But France had turned a corner. Napoleon’s concern was not to maintain liberty, equality and fraternity, but to exert his own control over all French holdings. As time would reveal, he fully intended to re-establish slavery on Saint Domingue. His wife was from a slave owning family. He sent an army of 20,000 to exert his will. After a prolonged conflict, Toussaint was betrayed to the enemy and placed in prison. Some historians tell us that Jean-Jacques Dessalines was partly responsible for his betrayal.

Toussaint’s most famous words were spoken at this time:

In overthrowing me you have cut down in Saint Domingue only the trunk of the tree of liberty; it will spring up again from the roots, for they are numerous and they are deep.2

Did the tree of liberty spring up? You be the judge. When Jean-Jacques Dessalines realized that the French did indeed plan to re-impose slavery on the island, he and his black army committed themselves to fight them to the death. In a desperate struggle, vastly outnumbered, Dessalines led them to victory, helped by a yellow fever epidemic that swept through the French forces. Finally, on December 4, 1803, the French general Rochambeau surrendered, and the independent republic of Haiti was formed with a new imperial constitution. Dessalines proclaimed himself Emperor Jacques I.

One of his first actions as Emperor was to kill all the white people on the island. Known as the 1804 Haiti Massacre, this took place during the first four months of the new year. Three to five thousand people were slaughtered and Emperor Jacques declared Haiti an all black nation. But without the giftedness and expertise of whites, the economy collapsed. The emperor imposed a system of “military agrarianism,” which most blacks saw as merely a new version of slavery.

One of his first actions as Emperor was to kill all the white people on the island. Known as the 1804 Haiti Massacre, this took place during the first four months of the new year. Three to five thousand people were slaughtered and Emperor Jacques declared Haiti an all black nation. But without the giftedness and expertise of whites, the economy collapsed. The emperor imposed a system of “military agrarianism,” which most blacks saw as merely a new version of slavery.

Dessalines also practiced discrimination against mulattoes and was eventually killed during a mulatto revolt on October 17, 1806, in Pont Rouge.

Today, Haiti has the second highest rate of slavery per capita in the world, after Mauritania.3 This is transformation?

Gabriel’s Rebellion

Spurred by the short-lived success of the Saint-Domingue rebellion, a plot grew up in the U.S. among slaves on the Prosser farm north of Richmond, Virginia. Gabriel Prosser, the most trusted slave of Tom Prosser, was selected to be leader. During the first half of the year 1800, secret plans were communicated throughout four surrounding counties.

Here was the plan: The killing would begin with Tom Prosser and other plantation owners north of Richmond. Then a contingent of slaves would make their way to the tobacco warehouses in Richmond and set them on fire. When the white people were down at the river trying to put the fire out, the main army of slaves would raid the arsenal in Richmond, kidnap governor James Monroe, and draw more slaves into a much wider revolt throughout the area.

But on August 30, the day of the planned insurrection, two things happened. First, two slaves informed Prosser’s neighbor of the plan. And second, that night, the storm of the century swept through Virginia, making all the streams impassible. Militias were dispatched. Slaves were arrested. The rebellion fell apart.

Thirty-five slaves were tried and hanged. But the rebellion had much wider consequences for the entire South. As reflected in the words of one John Randolph: “The accused have exhibited a spirit which, if it becomes general, must deluge the Southern country in blood.”4

Gripped by fear, the white population of the South took steps to prevent that deluge of blood. First, they got rid of all abolition societies. Second, they made it illegal for slaves to gather for religious purposes—no doubt because of the testimony that the slaves had planned to kill all white people “except Methodists, Quakers and Frenchmen.”5 Third, all freed slaves were required to leave the state. Fourth, teaching slaves to read or educating them was made illegal.

This surely was not the transformation any of the slaves had had in mind. And yet, today, our country is transformed, and not because of Gabriel’s rebellion. Slavery has been banished as an acceptable practice in Western nations. How did this happen? And what was it about those movements that made them successful?

Successful Abolition Movements

Successful abolition movements have gone unheralded in our society because they happened in a way that our society at present would not have preferred. Surely, this shows how a worldview shapes our perception of the past according to current values.

The first abolition movement in history occurred as the Gospel of the Kingdom spread west into Ireland in the fifth century. Thomas Cahill attempted to draw the attention of historians to one of the most neglected areas of Western history in How the Irish Saved Civilization. Cahill shows that Patrick, the first Christian evangelist to Ireland, initiated the abolition of slavery. “The greatness of Patrick is beyond dispute: The first human being in the history of the world to speak out unequivocally against slavery. Nor will any voice as strong as his be heard until the seventeenth century.”6

Cahill attributes this unique destiny to the fact that Patrick had been a slave, and therefore wouldn’t wish slavery on anyone. This is certainly true, but I believe it also traces to the type of Christianity that Patrick imbibed, which was not the “Salvation” Christianity of Rome, but the “Kingdom” Christianity practiced in the deserts of Egypt, and by the apostolic fathers of the Church prior to the Edict of Nantes in 313 AD.

For many years, I assumed that the British Church was the result of Roman Catholic evangelism. However, Rome had nothing to do with it. Rome had attempted to spread the gospel into Britain during the 4th century, failed, and withdrew from the arena. God had other plans. He raised up the Celtic Church.

The Edict of Milan in 313 made Christianity legal. Properties confiscated by the government to sustain the lavish lifestyle of emperors were returned to Christians. Suddenly, Christians could become wealthy and hold political office.

Eastern Church leaders saw that there was a danger here. Jesus did not recommend that Christians invest heavily in worldly power and wealth. So the theologian Athanasius wrote a biography as an antidote to worldliness: The Life of St. Anthony.

This book, which portrays a life utterly devoted to prayer and spiritual warfare, took the world by storm. When people saw the inner authority that emanated from the life of this desert hermit, many wanted to become desert hermits. This book was the single greatest influence in the formation of the Celtic Church. For example, it deeply influenced Martin of Tours, a revivalist who started Marmoutier, a house of prayer that provided the evangelistic vision that birthed the Celtic Church. For centuries, Celtic saints would make the pilgrimage to Tours to honor Martin as their spiritual father.

During the following generation, the influence of the Desert increased among the Celts. The first of the Desert Fathers to write down the wisdom of the Desert was Evagrius of Pontus. People went into the Egyptian desert so they could learn prayer. Henri Nouwen, in his book, The Way of the Heart, encapsulates the Desert Way in three words: Prayer, Silence and Solitude. But it was all about prayer. Silence and solitude were there merely as guardians of prayer.

Accordingly, Evagrius wrote: “If you are a theologian, you truly pray. If you truly pray, you are a theologian.” As far as the men and women of the Desert were concerned, Jesus died to obliterate the barrier between us and God. Prayer is the way to apply the Cross to our every day lives. Evagrius’s biographer summarizes: “Evagrius tends to equate the whole of Christian life with the life of prayer…. To pray without distraction equals to follow Christ.” The movement we are calling The Desert was one vast prayer movement.

Accordingly, Evagrius wrote: “If you are a theologian, you truly pray. If you truly pray, you are a theologian.” As far as the men and women of the Desert were concerned, Jesus died to obliterate the barrier between us and God. Prayer is the way to apply the Cross to our every day lives. Evagrius’s biographer summarizes: “Evagrius tends to equate the whole of Christian life with the life of prayer…. To pray without distraction equals to follow Christ.” The movement we are calling The Desert was one vast prayer movement.

Evagrius, in turn, had two disciples at his community in Nitria, Egypt, both of whom went to Gaul after the death of their tutor. John Cassian founded a house of prayer in Marseilles, and was instrumental in guiding an enormous prayer movement throughout Gaul. (Cassian was also a major influence in the life of the founder of the Benedictine monasteries in Italy: Benedict of Nursia.)

But an even more profound influence was his friend Germanus of Auxerre, one of the most under-rated and forgotten saints of the past, who literally brought the influence of the Desert to the British Isles. To begin with, he was the evangelist who brought the Gospel to Wales. And second, it was Germanus who trained Patrick, who took the Gospel to Ireland.

I am trying to show why it is that the Celtic Church did not have the accoutrements that we always associate with “Church.” They didn’t do pews and pulpits and stained glass windows. For the next 250 years the Celtic Church would consist almost entirely of houses of prayer. If you were a Christian leader, you started a house of prayer.

Where the Roman Catholic Church was trying to make the case that it IS the Kingdom of God on earth, by virtue of apostolic succession from Peter, the Celtic Church believed that, by prayer, we can invite “times of refreshing from the presence of the Lord” (Acts 3:19). The Kingdom of God comes when God bestows seasons of His Divine Presence in response to prayer by His Royal Priesthood. When God comes, He writes His laws on our hearts and gives us a new destiny, related to the King’s plans. I call this type of Christianity “By my Spirit” Christianity. It was the type of program followed by Jesus and the apostles. The Church becomes not a place to go on Sundays to hear someone preach. It becomes a midwife, giving birth to God’s Kingdom on earth. The purpose of the Church is to advance the Kingdom of God by prayer.

This method succeeded in winning the British Isles for Christ. Ireland abandoned the Druid faith and embraced Christ within the lifetime of Patrick, as Patrick himself tells us. Then the famous St. Columba sailed to Scotland, established a prayer community at the Isle of Iona, and won the Pictish people to Christ, so that Scotland became fully Christian (with the help of St. Mungo, who established a house of prayer which became the City of Glasgow). Then Aidan went to Northumbria to establish the house of prayer at Lindisfarne, to begin winning the Anglo-Saxons to Christ. Another group sailed back to the continent with Columbanus (only one of many to do so) to spread the gospel of the Kingdom back to Europe, even establishing a house of prayer at Bobbio in northern Italy. For 250 years, this house-of-prayer spirituality was all that the British people had ever known.

Then, in 597, Gregory the Great sent a Benedictine monk named Augustine to England to establish the Roman Church in Britain. This was the beginning of Mediaeval Christianity and the demise of Celtic Christianity. And what a contrast! Instead of relying on the power of God, the Roman Church had become adept at developing a religion of worldly power: political alliances with kings, conformity to a single standard enforced from the top, military warfare rather than spiritual warfare, and a religion of external impressiveness—fancy clothes and enormous buildings. I call this “Power and Might Christianity.” (This is not an anti-Catholic diatribe. Any Christian can choose the “Power and might” option. Protestants have been just as good at it as Catholics.)

It is significant that Celtic Christianity despised slavery and freed the British Isles from it, while Medieval (Roman) Christianity believed that slavery was a perfectly good way of making pagans into Christians. But this attitude toward slavery was only one ingredient of an entire lifestyle choice, a contrast between “By My Spirit,” and “Power and Might” spirituality. When Rome took over, The Desert went out of fashion. But Roman Christianity was not transformational. The Mediaeval period would become a sad tale of a church incapable of transforming anything. The worldly power it trusted in un-transformed the church into a worldly institution indistinguishable from other worldly institutions, a trend that reached its peak during the Renaissance years.

Now to the point: Patrick despised slavery not only because he had been a slave, but because slavery did not fit the “By My Spirit” understanding of Christianity that he had been taught. The life of self-surrender, listening to God, obedience to His voice and humility was the very opposite of the overbearing violence represented by slavery. To Patrick, the two lifestyles were incompatible.

Abolition was only one of many ways that prayer ushered in the Kingdom of God, which transforms many areas of life simultaneously. Let me summarize with a quote from Thomas Cahill: “The thirty-year span of Patrick’s mission in the middle of the fifth century encompasses a period of change so rapid and extreme that Europe will never see its like again. By 461, the likely year of Patrick’s death, the Roman Empire is careening in chaos. …(But) as the Roman lands went from peace to chaos, the land of Ireland was rushing even more rapidly from chaos to peace.”

- Transformation.

- And abolition.

The English Abolition Movement

The only abolition movements that succeeded in history are those that were initiated by God in His program for His Kingdom. They were the result of Christian prayer, leading to spiritual awakening, leading to social holiness. God is offended by slavery.

In order to achieve His objectives, God had to find Christians who were willing to reject Power and Might Christianity, surrender their lives to Him, and let the Holy Spirit turn them into instruments of His will. This happened in England during the Great Awakening, so that the Second Great Awakening became a major abolition movement that wiped out slavery throughout most of the earth. Then, in the very year that the English passed laws to use the English Navy to enforce Abolition throughout the world, God moved to America to do the same, using exactly the same methods. God’s methods are effective.

The English story began when in February of 1744, a young Freethinker from Chatham, ignoring his father’s advice, carelessly allowed himself to be pressed into the British Navy aboard the ship Harwich. But this particular Freethinker did not like being a sailor, and he showed it by his foul mouth, which delighted in ridiculing God at the top of his voice. So foul was his blasphemy that the other sailors began to warn him and complain to the captain.

This man made himself so unwelcome on board the Harwich that the captain traded him off to a slave-ship, The Pegasus, in which he was taken to Africa to become caught up in the slave trade of Gambia. The slave trade was not kind to him. He was often made to do the most menial tasks for the slave trader, Clow, and his black mistress. Gambia proved to be a seminary classroom on the subject of human depravity, and our Freethinker was learning the hardships of sin to the full.

After a year God mercifully released him from the accursed place, to sail aboard the ship Greyhound, which carried ivory, beeswax, wood and gold (not slaves) to the Caribbean, and then took its crew to England. Before it arrived in England, however, it encountered a storm that seemed to be sent from God to keep them from their destiny—or else drown them all. Why would God permit such a thing? He must be punishing someone on board the ship, they said to one another. All eyes turned to the likeliest culprit: our blaspheming Freethinker.

One night, while taking his turn at the helm, suddenly God was there. He didn’t say anything, but He was there, and our Freethinker was, in a moment, converted into a Christian. God was as real to him now as the steering wheel in his hand. The experience cleaned up his mouth instantly. Everyone on board noticed some kind of change in the man, but none could account for it. They also noticed that the storm was abating, and the Greyhound was now making progress toward England again, as described in Grace Irwin’s biography, Servant of Slaves.

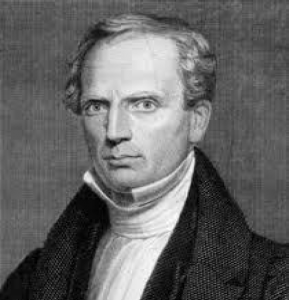

Our Freethinker, whose name was John Newton, resolved to become an Anglican clergyman. Today Newton is known as the author of the hymn, “Amazing Grace.” But during his lifetime, he was a key player in the abolition of slavery. By the way, the English Great Awakening was in full swing, and people were encountering God everywhere.

Our Freethinker, whose name was John Newton, resolved to become an Anglican clergyman. Today Newton is known as the author of the hymn, “Amazing Grace.” But during his lifetime, he was a key player in the abolition of slavery. By the way, the English Great Awakening was in full swing, and people were encountering God everywhere.

Conversion to Christ did not automatically divorce Newton from the slave industry. At first he thought, “It’s a bad job, but someone’s got to do it.” It would take several years and an important encounter with John Wesley before Newton would see the issue clearly.

Thirty-four years later, in 1788, Newton published a broadside pamphlet, Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade that opened a window for English people into the true horrors of slavery. Every member of Parliament received a copy, and the pamphlet went viral. Because Newton was speaking from experience, and because he was so highly respected as a clergyman, his reflections had a unique authority to cut through political rhetoric.

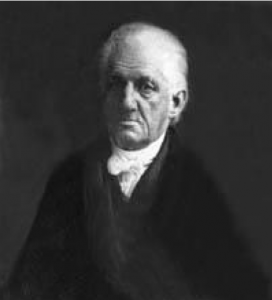

But it was John Wesley more than anyone who was responsible for converting a spiritual awakening (the English Great Awakening) into a movement of Kingdom transformation. He did this by establishing a network of small groups called Methodist Societies. These were home groups to which Wesley gave explicit instructions: the group leader was to tell the other eleven people in his group how he had sinned and been tempted to sin since their last meeting, and then everyone else in the group would do the same, with each person receiving prayer for their area of temptation. Methodism was a holiness movement, and people did not let personal embarrassment get in the way of the pursuit of holiness.

But it was John Wesley more than anyone who was responsible for converting a spiritual awakening (the English Great Awakening) into a movement of Kingdom transformation. He did this by establishing a network of small groups called Methodist Societies. These were home groups to which Wesley gave explicit instructions: the group leader was to tell the other eleven people in his group how he had sinned and been tempted to sin since their last meeting, and then everyone else in the group would do the same, with each person receiving prayer for their area of temptation. Methodism was a holiness movement, and people did not let personal embarrassment get in the way of the pursuit of holiness.

But Wesley did not make a distinction between personal holiness and public holiness. Slavery was just as much an affront against the holiness of God as pornography or cursing. All Methodists were forbidden from practicing slavery in any form. Wesley also had an irritating way of believing that God could even reform the Anglican Church. He had an extraordinary influence on Anglicans (like John Newton) some of whom ended up in the London suburb of Clapham.

A key influence in Clapham was an evangelical Anglican named Henry Venn, who sparked a prayer movement. Venn urged all Christians to follow Jesus by spending significant personal time with God in prayer at home early in the morning.

Clapham was a wealthy suburb full of industrialists and members of Parliament—not promising raw material from which to forge a great awakening. Yet Clapham became the center of the Second Great Awakening in England, and one focus of that awakening was the abolition of slavery. At Clapham, God forged together the prayers of Henry Venn, the pamphlet-testimony of John Newton and the raging holiness of John Wesley, and raised up from this furnace a Member of Parliament named William Wilberforce to personally take on one of the most evil and demonic connivances in human history. As Wesley himself wrote to Wilberforce in the last letter Wesley wrote to anyone:

Unless God has raised you up for this very thing, you will be worn out by the opposition of men and devils: But if God be for you, who can be against you? Are all of them together stronger than God? Oh! Be not weary of well-doing. Go on in the name of God and in the power of His might, till even American slavery, the vilest that ever saw the sun, shall vanish away before it.8

William Wilberforce was the voice that God used to articulate the case against slavery in Parliament. But the success of the movement to transform the world from this curse was the power of the Holy Spirit writing God’s laws on many hearts in answer to prayer. By 1807, the Slave Trade Act outlawed slavery in England. In 1826, Wilberforce resigned from Parliament because of ill health, but the abolition movement continued on until the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 abolished slavery throughout the British Empire worldwide. In fact, the British Navy became a police force for the entire globe, stopping slave ships and freeing slaves at will. Then God began to target American slavery.

American Slavery, the Vilest of Them All

Let’s go back a little. Slavery in America was the product of Power and Might Christianity as practiced by the Anglican Church under control of the Stuart kings of England. It was Archbishop William Laud who was appointed by Charles I (son of King James) to head up the Lords of the Plantations, which fixed policies for the distribution of land in the colonies. By these policies, the rich got richer and the poor got poorer. Soon almost all of Virginia was owned by a handful of Virginia tobacco planters, who gained control of the new government in Williamsburg. It was Charles II (grandson of James), who suggested that these planters begin purchasing slaves from Africa. His thinking went like this: English people are Christians and should not become slaves, but black people are heathen, and Christians can enslave them.9

This family of Stuart kings—James, Charles I and Charles II—had horned their way into the English Church by promoting the doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings, a doctrine opposed by Reformers like John Calvin in the Geneva Bible. (That’s why James wanted a new Bible.) Then they dictated their policies and their morals to the Archbishops of Canterbury to infiltrate the entire Church. To say that this was a poisonous influence on the Church is the greatest understatement in all of history. For over a century, these kings persecuted wave after wave of Christians touched by the Spirit of God—Presbyterians, Quakers and Puritans, who then fled Britain and came to America, settling primarily in the North. These were the Christians who understood the power of prayer and the influence of the Holy Spirit writing laws on hearts. The Anglicans, who settled primarily in the American South from their beginnings at Jamestown, absolutely did not understand this principle. With few exceptions, they believed in the power of the sword, and they loved their military prowess.

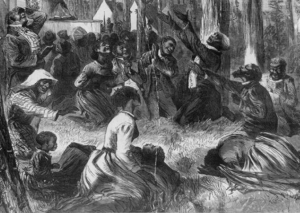

I have already pointed out that by 1802, throughout the South, it was illegal for slaves to gather together for prayer, or pursue Jesus, except by going with their masters to hear the official state-sponsored version of Christianity, which was Anglican. Bad things would happen to slaves caught in unapproved prayer meetings. (The situation was no different from Scottish Covenanters a hundred years before.)

Yet, as Princeton historian Albert Raboteau has shown, black slaves took the risk. God was raising up in slave camps one of the greatest prayer movements in American history. One slave reflected on those years: “Meetings back there meant more than they do now. Then everybody’s heart was in tune, and when they called on God they made heaven ring.”10 Sometimes, slaves would use cooking kettles for an impromptu prayer room. Putting their heads inside kettles, one to three persons at a time while lying on the ground, their prayers could not be heard by white people. They could pray at the top of their lungs, and no one would hear.11

Slave prayer reached a culmination in the ministry of a Presbyterian preacher named John Lafayette Girardeau. Girardeau’s father was Hueuenot, his mother Scottish Presbyterian. He started his ministry at Anson Street Presbyterian Church in Charleston, a church that consisted of 47 members, almost all slaves. When Girardeau saw the spiritual climate in Charleston, he decided not to preach there, but to hold nothing but prayer meetings with his slave congregation. After months of this, Girardeau had an experience of something coming down from above and striking him on the forehead. From that day, in 1857, a great prayer anointing began in the USA. This enormous prayer movement is usually thought to have started in New York City under the ministry of Jeremiah Lanphier. However, the experience of Girardeau preceded Lanphier, and the great prayer movement of 1858 can justifiably be traced to black slaves in Charleston. Immediately, people began to flock to Anson Street Church, which had to move into larger facilities. Soon, Girardeau became known as the Spurgeon of the South. What I want to show is that God was bringing about extraordinary prayer during the first sixty years of the 19th century in America. This prayer was producing spiritual awakening across the land. Now let’s look at how that awakening produced an abolition movement.

Slave prayer reached a culmination in the ministry of a Presbyterian preacher named John Lafayette Girardeau. Girardeau’s father was Hueuenot, his mother Scottish Presbyterian. He started his ministry at Anson Street Presbyterian Church in Charleston, a church that consisted of 47 members, almost all slaves. When Girardeau saw the spiritual climate in Charleston, he decided not to preach there, but to hold nothing but prayer meetings with his slave congregation. After months of this, Girardeau had an experience of something coming down from above and striking him on the forehead. From that day, in 1857, a great prayer anointing began in the USA. This enormous prayer movement is usually thought to have started in New York City under the ministry of Jeremiah Lanphier. However, the experience of Girardeau preceded Lanphier, and the great prayer movement of 1858 can justifiably be traced to black slaves in Charleston. Immediately, people began to flock to Anson Street Church, which had to move into larger facilities. Soon, Girardeau became known as the Spurgeon of the South. What I want to show is that God was bringing about extraordinary prayer during the first sixty years of the 19th century in America. This prayer was producing spiritual awakening across the land. Now let’s look at how that awakening produced an abolition movement.

The American Anti-slavery Movement

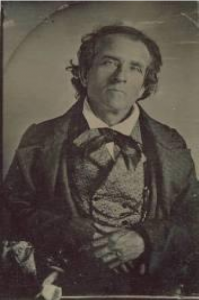

Just when it looked like the Second Great Awakening was winding down in America, along came Charles Finney in the 1820’s. Finney was an abolitionist, but he rarely, as an evangelist, preached abolition. He was perhaps the first Christian leader in the U.S. to teach on the baptism with the Holy Spirit as the power of God in ministry. And he had a great deal to say in his Revival Lectures about the necessity of prayer. Prayer and the Holy Spirit! Finney was definitely one of those “by my Spirit” Christians who believed in relying on God’s power and presence in ministry. How else, to explain what happened?

Mysteriously and wonderfully, from the ranks of those converted under Finney came a host of devout, give-‘em-no-quarter abolitionists.

Many of Finney’s young converts ended up at Lane Theological Seminary, a new school under the leadership of Lyman Beecher in Cincinnati. In 1834, the student body held a debate about slavery that lasted some 18 days. A key turning point in this debate occurred when James A. Thome, son of a Kentucky slaveholder, described in detail the cruelties inflicted on slaves from his own family’s experience. As with John Newton, the satanic cruelty of slavery, covered over by a thin veneer of Christianity, had to be revealed by a credible witness. Another turning point was achieved by Rev. Dr. Samuel Cox, who called the Colonization Society, which sought to move all slaves back to Africa, “a society of kidnappers.” He had been an agent of the Society until he learned that slaves didn’t want to return to Africa.

The debate produced the beginning nucleus of what was to become the American Anti-slavery Society. Historian William Lee Miller describes the kind of people who managed to push our country off the horns of dilemma about slavery beginning in 1834:

The new abolitionism had its most energetic support in the areas where the revivalism of the time was strongest…

At the center of the new abolitionism were young Presbyterian and Congregational ministers of a trailblazing sort….

…Perhaps “ministers” is not the right word for them. Many were indeed converted in some high-octane religious setting; did go to seminaries; were ordained. They all did make their antislavery case in distinctly Christian terms—very much so. They did indeed have the style and approach of the preacher or evangelist. Nevertheless they characteristically did not serve churches. They traveled; they spoke; they wrote; they distributed tracts; they edited journals; they agitated; they were mobbed. They did those things full-time.12

Many people today do not make the connection between “revival” and “social action.” But the cause of “revival” becomes shallow and self-centered unless it results in God’s laws being written on human hearts. And the cause of justice becomes easily misguided unless the passion for justice is rooted in the grief of God over human cruelty and lovelessness.

Lyman Beecher was a product of the Second Great Awakening, but he did not comprehend where God was taking things. He could not make the transition from revival to transformation. He believed in abolishing slavery, if it could be done easily and in a dignified way without upsetting anybody’s applecart. But now the slave issue was causing division at his seminary. Slave-holding donors were withdrawing their support; mobs were coming over from Kentucky agitating against the students. Soon the Trustees forbade all further discussion of slavery. And Beecher refused to offer classes to African-Americans. Instantly, fifty students left Lane and transferred to Oberlin College.

Why Oberlin? Charles Finney was there (a teacher and future president). And Oberlin was doing what Lane could not manage: it was living by the principle, “In Christ there is neither male nor female, slave nor free.” Oberlin was fast becoming the first institution in America to welcome people of all races and both genders. In other words, they were willing to translate revival into transformation. It was also the place where Theodore Dwight Weld, the acknowledged leader of those 50 students, got his start in the abolition of slavery. Weld wrote the book that did more to expose the evils of slavery than any other writing of its time: American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses. This book, and The Life of Frederick Douglas were the two books that spurred moral indignation over the issue by exposing to public view the raw evil of the institution. God works not by violent rebellion, but by writing His laws on human hearts. Slavery does not belong in the Kingdom of God. Americans began to see this in larger numbers.

But we are not done with Lane Seminary in Cincinnati. Lyman Beecher had 13 children, and they grew up in the midst of the abolition controversy. Because they were exposed to the actual conditions of black slaves, all of Lyman’s children grew up to become abolitionists, many at personal cost to themselves.

Lyman’s second daughter, Hattie, married to professor Calvin Stowe, was an occasional writer of Christian articles. Early in the 1840’s, she had the following experience:

On one memorable occasion, near the Cincinnati waterfront, Mrs. Stowe had seen a slave family torn apart, the father sold to one buyer, the mother to another, and their three-year-old child left without parents. Unable to tolerate the injustice, Mrs. Stowe borrowed the money to buy the child and was able to reunite her with her mother. But thousands of slaves were being similarly treated like cattle, and there seemed to be nothing that an impoverished housewife and part-time writer of minor words could do to help them.13

In September of 1850, Hattie’s sister-in-law wrote to her: “Now, Hattie, if I could use a pen as you can, I would write something that would make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.” (p. 64) Using her many encounters with slavery as material, combined with her reading of The Life of Frederick Douglas, and Weld’s Slavery As It Is, she set about writing a novel.

In September of 1850, Hattie’s sister-in-law wrote to her: “Now, Hattie, if I could use a pen as you can, I would write something that would make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.” (p. 64) Using her many encounters with slavery as material, combined with her reading of The Life of Frederick Douglas, and Weld’s Slavery As It Is, she set about writing a novel.

Hattie had been raised to believe that novels (like short stories and the theater) were iniquitous and depraved, the sort of reading true Christians did not do. By writing a novel, she was flying in the face of her father and the countless sermons he had preached on the subject.

And it was not a woman’s world. Hattie was a contemporary of the novelist George Eliot, pen name for Mary Ann Evans, who took a man’s name because women were not considered fit for anything but crocheting and nursing babies.

But God was producing a new world (“neither male nor female, slave nor free”)—and not only at Oberlin College. So Harriet Beecher Stowe produced a novel under her own name: Uncle Tom’s Cabin. “I could not control the story,” she later wrote. “It wrote itself. I the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin? No, indeed. The Lord Himself wrote it, and I was but the humblest of instruments in His hand.”

The contract was signed on March 13, 1852, and the entire first printing of 3,000 sold on the first day of publication in April. Before the year’s end, 120 editions had been printed with total sales of 350,000. Within two years, the book had been published in French, Spanish, Danish, Finnish, Dutch, Flemish, Polish, Russian, Bohemian, Hungarian, Serbian, Armenian, Illyrian, Romaic, Wallachian, Welsh, and Siamese. Ultimately, it was published in 40 languages. It was the greatest publishing wonder in the history of the American press, rivaling the popularity of the English writer, Charles Dickens.

Then came the play. Harriet was approached by a famous playwright, Asa Hutchinson, requesting permission to dramatize Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She refused, explaining that she did not wish to encourage Christians to get into the habit of attending theater.

A less famous (and less conscientious) playwright named George Aiken decided to write the play with or without her permission. The dramatic version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, written and produced without permission of the author, became the most successful play in the history of American theater. The play was produced continuously, somewhere in the U.S., from 1853 to 1934. It was also translated into seventeen languages, becoming easily the greatest dramatic success in the world. Yet Harriet received not one penny of royalties. She didn’t seem to care.

What mattered to Harriet was that God was using the novel she wrote to birth a slaveless nation, and abolition of slavery was in her mind a necessary ingredient of the Gospel of the Kingdom.

There is no question but that it was this novel that won the hearts and minds of the majority of Americans to reject slavery, as being unworthy of Christ. That, at least, seems to have been the opinion of Abraham Lincoln, according to the story told by Harriet’s brother, Charles. Charles and Harriet one day visited the president in December of 1862, and the President blurted out: “So this is the little lady who made this big war.”15

Here was a novel written by a woman who didn’t believe in novels to a public who didn’t believe in women authors, and it changed the world’s attitude about slavery, all in a matter of a few years. Until then, most people believed that slavery was a normal and necessary part of life, and had believed this for millennia, since the dawn of recorded history. After that, most people came to believe in abolishing slavery as a diabolical curse that Christian people must not tolerate.

The life of Harriet Beecher Stowe is one of the greatest testimonies in American history of the transforming power of Christ in a nation. Yet today, it has been almost completely forgotten.

The Issue Behind It All

Many lessons could be gleaned from these stores about the abolition of slavery. But the bottom line is this: God is not just interested in getting us to heaven. He also wants to transform this world so that it becomes the Kingdom of God—“on earth as it is in heaven.” Jesus is King here, and as we pray, we wield a kingly iron scepter—His scepter—over the nations. (Rev. 2:26-27). Jesus is coming back to rule the nations, and in the meantime, we are permitted to see “times of refreshing from the presence of the Lord.” That is God’s promise, reflected in the second sermon of the Apostle Peter. And it is the basis of all hope for transformational revival.

Today, slavery is making a comeback. And the same God who delivered the United States from it in the 1860’s can do it again, if God’s royal priesthood will pray.

1 “Haitian Heroes,” hougansydney.com.

2 From the Wikipedia article on Toussaint Louverture. Quoted from Elizabeth Abbott: Haiti: An insider’s history of the rise and fall of the Duvaliers. Simon & Shuster, p. viii.

3 “Ten Statistics on Slavery Today,” borgenproject.org.

4 Virginius Dabney, Richmond: The Story of a City, Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1990, p. 57.

5 Ibid., Dabney, p. 56.

6 Thomas Cahill, How the Irish Saved Civilization, New York: Doubleday, 1995, p. 114.

7 Ibid., pp. 123-124.

8 John Wesley to William Wilberforce, Feb. 24, 1791.

9 Anthony Parent, Foul Means: The Formation of a Slave Society in Virginia, 1660-1740. Anthony Parent writes: “Since the English used non-Christian affiliation as justification for enslavement and associated Protestant Christianity with liberation, blacks and Indians seeking redress from slavery by pleading their Christianity provided whites with a dilemma in creating a closed racial society.” This provided powerful motivation against introducing slaves to the claims of Christ, especially in the early years, when slave owners and traders were still trying to reconcile slavery with the Gospel.

10 Albert Raboteau, Slave Religion, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978, p.217.

11 Does this explain why William Seymour at Azusa used to put his head inside an orange crate when he prayed?

12 William Lee Miller, Arguing About Slavery, New York: Knopf, 1997, pp. 80-81.

13 Noel B. Gerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Biography, New York: Praeger, 1976, p. 55.

14 Ibid., p. 69.

15 Ibid., p. 163.